Providing problem solving and educational information for topics related to industrial steam, hot water systems, industrial valves, valve automation, HVAC, and process automation. Have a question? Give us a call at (800) 892-2769 | www.meadobrien.com

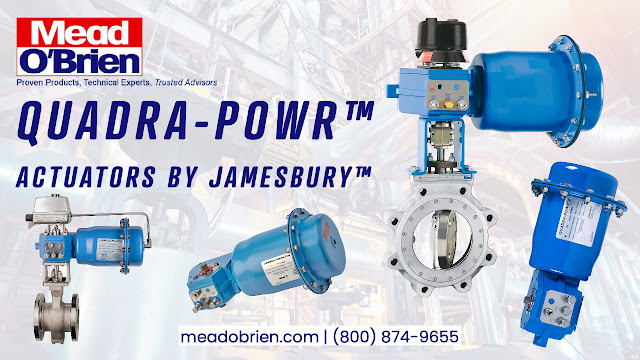

Jamesbury™ Quadra-Powr™ Spring Diaphragm Quarter Turn Actuators for Use in Both Modulating Control and On-Off Service

- Rolling diaphragm for minimum friction

- Low friction bearings – factory lubricated for lifetime

- Field reversible for spring to open or close simply by flipping actuator over

- Safety contained springs prevent hazards of inadvertent ejection during maintenance

- Corrosion resistant – two layer epoxy and polyurethane paint with stainless steel fasteners

- Adjustable stops for both open and closed positions

- Wide input pressure range – up to 7 bar (100 psi)

Industrial Actuators, Valves, and Positioners

Valves regulate fluid flow to provide accurate control and safety in any given process system, and methods of adjusting valve position are always required.

Commonly, valves are operated with handwheels or levers, although some must be regularly opened, closed, or throttled. In certain conditions, it is not always practical to position valves manually; hence actuators are employed instead of hand wheels or levers.

An actuator is a mechanism that moves or regulates a device, such as a valve. Actuators decrease the requirement for people to operate each valve manually. Valves using actuators can remotely control valve position, particularly crucial in applications where valves open and close or modulate fast and precisely.

Pneumatic, hydraulic, and electrical actuators are the three fundamental types.

- Pneumatic actuators employ air pressure to generate motion and are probably the most prevalent type of actuator utilized in process systems.

- Actuators powered by a pressurized fluid, such as hydraulic fluid, are called hydraulic actuators. Typically, hydraulic actuators of the same size produce more torque than pneumatic actuators.

- Electric actuators generate motion using electricity. Actuators usually belong to two broad categories: solenoid or motor-driven actuators.

Actuators position valves in response to controller signals and can be positioned rapidly and precisely to accommodate frequent flow variations. The instrumentation systems that monitor and respond to fluctuations in plant processes include controllers. Controllers receive input from other instrumentation system components, compare that input to a setpoint, and provide a corrective signal to bring the process variable (such as temperature, pressure, level, or flow).

You have a control valve when actuators pair with flow-limiting or flow-regulating valves. Generally speaking, control valves automatically restrict flow to provide accurate flow to a process to maintain product quality and safety.

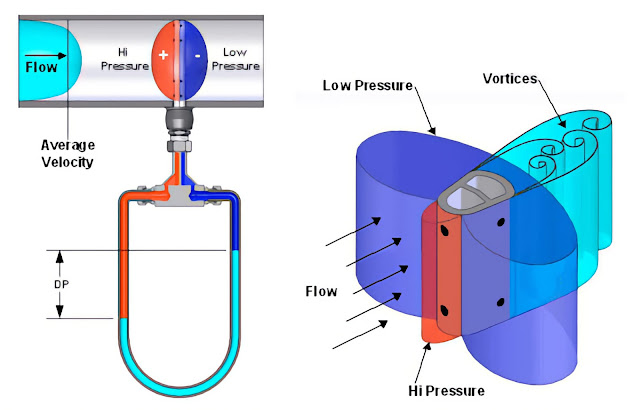

Control valves can be linear, where the stem moves the valve disk up and down like globe valves, or rotational. Rotary control valves include butterfly valves, which open or close with a 90-degree rotation. The pneumatic diaphragm and electric actuators are the most prevalent on linear and rotational control valves.

Some valves require long stem travel or substantial force to change position. A piston actuator's higher torque is preferable to diaphragm actuators in these situations. Examples of piston actuators are rack and pinion and scotch-yoke designs.

Single-acting piston actuators control the air pressure on one side of a piston, and with higher air pressure, the piston moves within the cylinder and turns the valve. The air on the opposite side of the piston exits the cylinder via an air vent. With decreased air pressure, the spring expands, causing the piston to move in the opposite direction.

If air pressure falls below a predetermined threshold or is lost, the spring will push the piston to the desired position, referred to as the "fail" position (open or closed).

A double-acting piston actuator lacks a spring and has air supply ports on both ends of the cylinder. Increasing air pressure to the supply port moves the valve in one direction. Higher pressure air entering from the opposite supply port pushes the valve in the opposite direction. Filling the cylinder with air and releasing air from the cylinder is regulated by a device known as a positioner.

Typically, the control of pneumatic actuators occurs from air signals from a controller. Some actuators react directly from a controller, for instance, a pneumatic 3-15 PSI controller output. Sometimes, a controller signal alone cannot counteract a valve's friction or the process media's fluid pressure. This situation requires a separate, high pressure air supply and modulating it with a pneumatic or electro-pneumatic positioner. These devices regulate a high pressure air supply to ensure that an actuator has enough torque to position a valve accurately. The positioner responds to a change in the controller's air, voltage, or current signal and proportions the high pressure air to the actuator. Connecting the actuator stem to the positioner is a mechanical linkage. This mechanical connection is also known as a feedback connection. The link moves as the actuator stem moves up, down, or rotationally. The location of the connection informs the positioner when sufficient movement coincides with the controller's air signal. The controller's signal transmits to the positioner instead directly to the actuator, and the positioner regulates the air supply provided to the actuator.

Like other process components, actuators are prone to mechanical issues. Since actuator issues can negatively impact the operation of a process, it is essential to be able to recognize actuator issues when they occur. Frequently, an operator can notice an actuator fault by comparing the valve position indication to the position specified by the controller. For instance, if the position indicator shows the valve closed, but the flow indicator on the controller indicates that flow is still passing through the valve, the valve seat and disc are likely worn, enabling leakage through the valve.

Because there are so many different styles and designs of actuators, positioners, and valves and so many industrial applications, the combination possibility matrix is vast. You must discuss your application with a knowledgeable, experienced valve expert. The success of your project in terms of product quality, system cost, maintenance, and safety depends upon it.

Mead O'Brien

(800) 874-9655